Hypoglycemia Risk Calculator

This tool helps you understand your risk of hypoglycemia unawareness when taking insulin and beta-blockers. Based on the latest medical research, it provides personalized safety recommendations.

Your Information

Risk Assessment

When you're managing diabetes with insulin, your body is already dancing on a tightrope. One wrong step-skipping a meal, overdoing exercise, or miscalculating a dose-and your blood sugar can plummet. Now add a beta-blocker into the mix, and that tightrope gets even narrower. For many people with diabetes, especially those with heart disease, beta-blockers are essential. But when combined with insulin, they can quietly erase the warning signs of low blood sugar. This isn’t just a theoretical risk. It’s a real, life-threatening interaction that’s happening in hospitals and homes across the country.

What Happens When Insulin Meets Beta-Blockers?

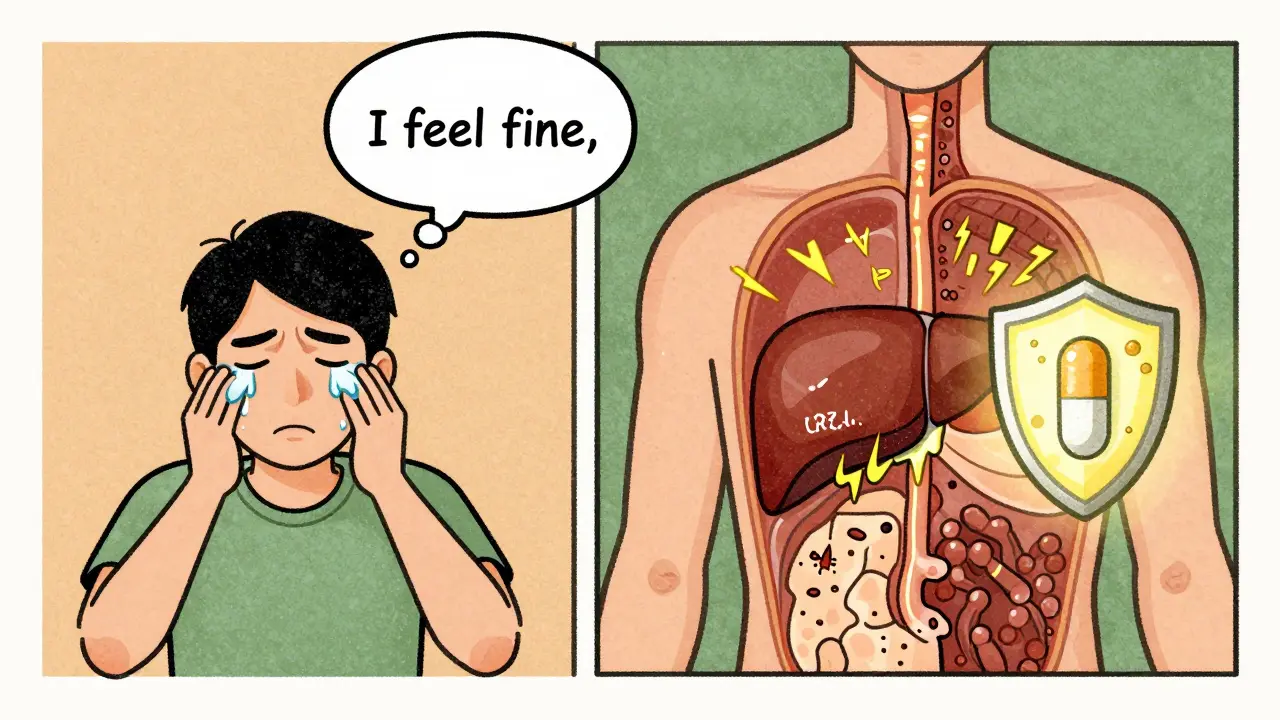

Insulin lowers blood sugar. That’s its job. But your body has backup systems to stop it from going too low. When glucose drops, your nervous system kicks in: your heart races, you start to shake, you sweat. These are your body’s alarms. They tell you: eat something now.

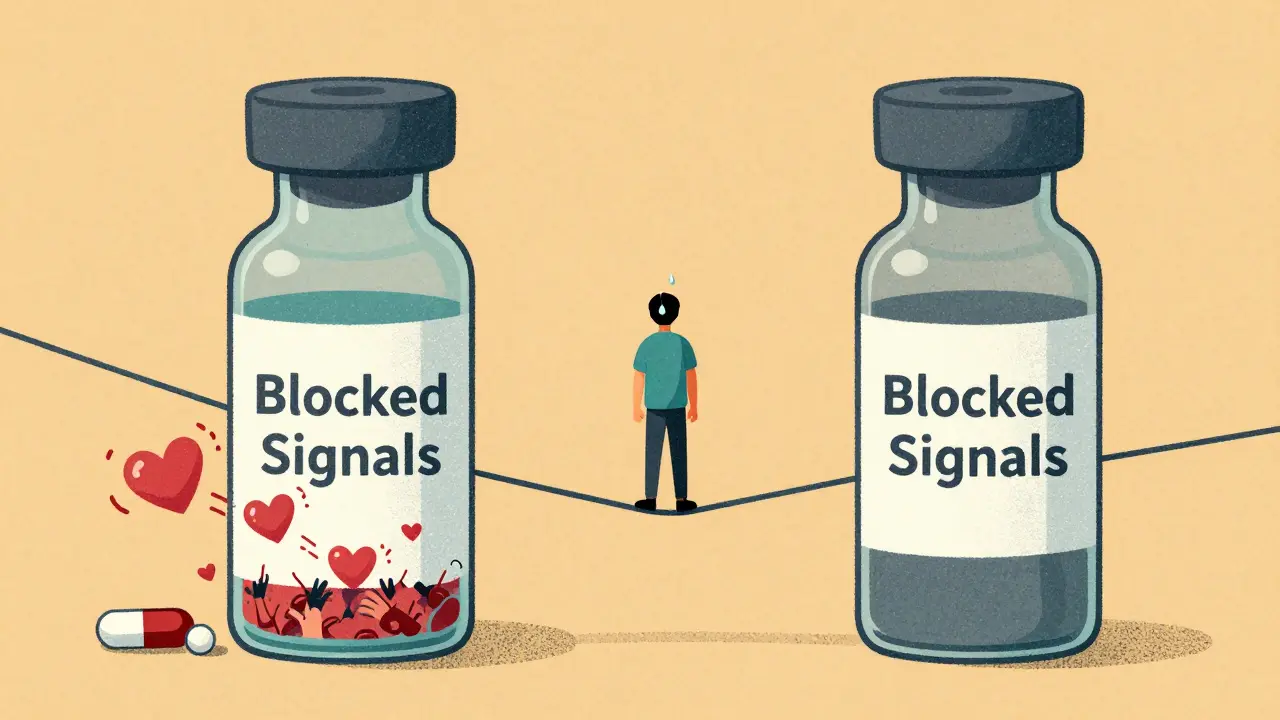

Beta-blockers, used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, or irregular heart rhythms, block those alarms. They stop the adrenaline surge that causes trembling and a fast heartbeat. That sounds helpful for heart patients-but for someone on insulin, it’s dangerous. You lose the early warning signs. You don’t feel your blood sugar dropping until it’s too late.

This isn’t just about missing a shaky hand or a racing pulse. It’s about hypoglycemia unawareness-a condition where your body no longer recognizes low blood sugar until you’re confused, dizzy, or unconscious. Studies show that up to 40% of people with type 1 diabetes develop this over time. Add a beta-blocker, and that risk spikes.

Not All Beta-Blockers Are the Same

There’s a big difference between types of beta-blockers. Some hit every beta-receptor in your body. Others are more selective. That matters a lot when you have diabetes.

Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol block both beta-1 and beta-2 receptors. Beta-2 receptors are found in the liver and muscles, where they help release stored glucose when blood sugar drops. Block those, and your body can’t fight back. That’s why non-selective beta-blockers are riskier-they don’t just hide the symptoms. They stop your body from correcting the low.

Cardioselective beta-blockers like metoprolol and atenolol mainly target the heart. They’re safer-but still risky. Even these can mask your heart racing and trembling. And here’s the catch: they don’t stop sweating. That’s your last line of defense. Sweating is triggered by a different system (acetylcholine, not adrenaline), so if you start to sweat for no reason, it could be your body screaming that your blood sugar is crashing.

Then there’s carvedilol. It’s not just a beta-blocker. It also blocks alpha receptors, which helps improve insulin sensitivity. Studies show carvedilol is linked to fewer hypoglycemic episodes than metoprolol. In one 2022 analysis, patients on carvedilol had 17% fewer severe low blood sugar events. For someone with diabetes and heart disease, carvedilol might be the smarter choice.

Why Hospital Stays Are High-Risk

Most dangerous hypoglycemia events happen in hospitals. Why? Because that’s where insulin doses get changed, meals get delayed, and beta-blockers are often started or adjusted-all at once.

Research shows that 68% of hypoglycemia events tied to beta-blockers happen within the first 24 hours of hospital admission. Patients on insulin and beta-blockers are checked less frequently than they should be. Nurses might check glucose every 6 or 8 hours. That’s too slow. When your body can’t warn you, you need checks every 2 to 4 hours.

And it’s not just about insulin. Even if you’re not on basal insulin, beta-blockers alone can increase hypoglycemia risk by 2.3 times. That’s because they interfere with your liver’s ability to release glucose. Your body can’t make up for the drop. That’s why the American Diabetes Association recommends tighter monitoring for anyone on insulin and beta-blockers in the hospital.

What You Can Do: Practical Safety Steps

If you’re on insulin and beta-blockers, you need a plan. Here’s what works:

- Check your blood sugar more often-especially before meals, before bed, and if you feel off. Don’t wait for symptoms. Use a glucometer even if you feel fine.

- Know your sweating. If you break out in a cold sweat without exertion or heat, treat it like a low. Eat 15 grams of fast-acting carbs-glucose tablets, juice, or candy-and recheck in 15 minutes.

- Ask your doctor about carvedilol. If you’re on metoprolol or atenolol and have had low blood sugar before, ask if switching could help.

- Avoid non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol or nadolol if you have hypoglycemia unawareness. The risk isn’t worth it.

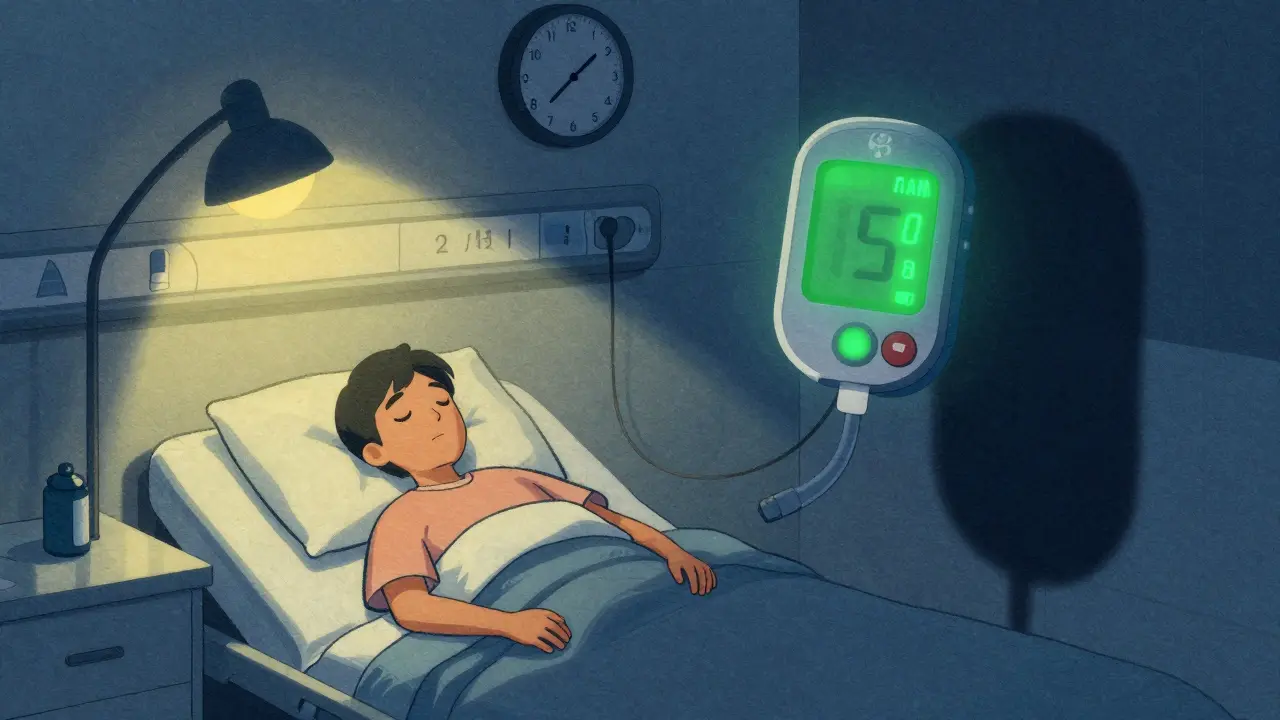

- Use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). CGMs have cut severe hypoglycemia events by 42% in people on beta-blockers. They alert you before your blood sugar drops too low-even while you’re sleeping.

Many people think, “I’ve never had a low before, so I’m fine.” But hypoglycemia unawareness builds slowly. One low blood sugar episode can make the next one harder to feel. It’s a snowball effect.

Long-Term Risks and Real Numbers

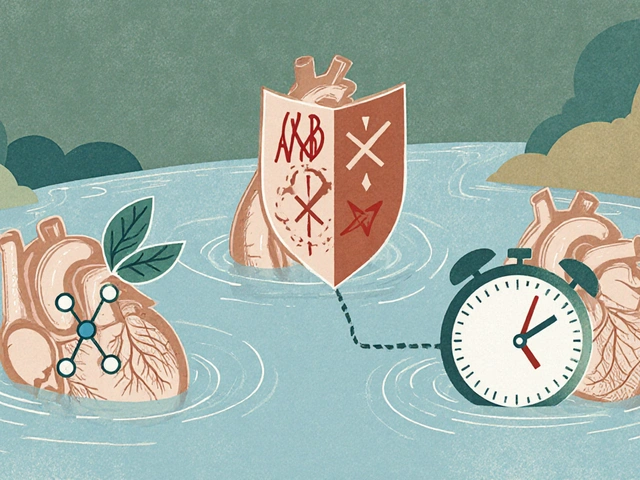

It’s not just about feeling dizzy. Severe hypoglycemia can lead to seizures, coma, or even death. Studies show that people on selective beta-blockers and insulin have a 28% higher risk of dying from a hypoglycemic event than those not on beta-blockers. That’s not a small number.

And yet, beta-blockers save lives. In people who’ve had a heart attack, they cut the risk of dying again by 25%. So stopping them isn’t the answer. The answer is smarter use.

One big study-the ADVANCE trial-followed diabetic patients for five years and found no difference in severe low blood sugar between those on atenolol and those on placebo. That’s reassuring for long-term outpatient care. But hospital data tells a different story. The danger isn’t always in the daily routine. It’s in the sudden changes: new meds, illness, surgery, skipped meals.

What’s New in 2026?

Science is catching up. The DIAMOND trial, launched in 2023, is looking for genetic markers that predict who’s most likely to develop hypoglycemia unawareness on beta-blockers. The goal? Personalized prescribing. In the future, a simple blood test might tell your doctor: “This patient should avoid metoprolol. Try carvedilol instead.”

Meanwhile, CGM use has jumped 300% since 2018 among high-risk patients. That’s not just tech hype. It’s saving lives. Real people are waking up before their blood sugar crashes. They’re avoiding ER visits. They’re sleeping through the night without fear.

Some experimental treatments are being tested too-like drugs that block opioid receptors or stimulate adrenaline pathways. But right now, the best tools are simple: better monitoring, smarter drug choices, and patient education.

Bottom Line: Safety Over Assumptions

Insulin and beta-blockers together aren’t automatically dangerous. But they’re a high-risk combo. You can’t assume you’ll feel it coming. You can’t rely on your body to warn you. You need to be proactive.

If you’re on both, talk to your doctor. Ask: Is this the right beta-blocker for me? Should I switch to carvedilol? Do I need a CGM? Am I checking my blood sugar enough?

And if you’re a caregiver, a nurse, or a family member-watch for sweating. It’s the one sign that doesn’t get blocked. Don’t ignore it. Treat it like a low. Every time.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about control. You can manage your diabetes. You can protect your heart. But you have to know the risks-and act on them before it’s too late.

Vinayak Naik

January 7, 2026 AT 00:18Man, this post hit different. I’m on metoprolol for AFib and insulin for T1D-never realized my sweats were the only alarm left. Now I check my CGM every 90 mins even when I feel fine. That 17% drop in lows with carvedilol? Game changer. My doc laughed when I asked to switch, but now he’s the one bringing up the study.

Beth Templeton

January 7, 2026 AT 06:48So you’re telling me sweating is the only warning left? Cool. So basically I’m just a robot waiting for a system crash.

Gabrielle Panchev

January 8, 2026 AT 22:06Actually, I think this whole narrative is dangerously oversimplified. First, not everyone on beta-blockers has diabetes-so why are we acting like this is a universal crisis? Second, the ADVANCE trial showed no increased risk in outpatient settings, so why are we panicking about hospital data as if it applies to daily life? And third-have you considered that CGMs are expensive, inaccessible, and often inaccurate? Not everyone can afford to ‘just get a CGM’ like it’s a new phone. This post reads like a pharma ad disguised as patient advocacy.

Also, the claim that non-selective beta-blockers are ‘riskier’ ignores that some patients respond better to propranolol for migraines or anxiety. Do we just toss out effective meds because they’re inconvenient for diabetics? That’s not medicine-that’s performative caution.

And let’s not forget: hypoglycemia unawareness develops over years of repeated lows, not because of beta-blockers alone. Blaming the drug is lazy. The real issue? Poor glycemic control, lack of education, and over-reliance on tech instead of learning your body. I’ve been on insulin for 32 years. I’ve never had a severe low. I don’t use a CGM. I eat regularly. I monitor. I adjust. It’s not magic. It’s discipline.

Also, carvedilol isn’t some miracle drug-it can cause fatigue, dizziness, and fluid retention. And yes, I know the 2022 study. But it was retrospective. Small sample. No long-term outcomes. We need RCTs, not blog posts with percentages.

And why is everyone ignoring that beta-blockers reduce mortality in post-MI patients by 25%? Are we really going to trade cardiac survival for the *possibility* of undetected lows? That’s not safety-that’s fear-driven medicine.

Also, the author says ‘don’t wait for symptoms’-but if you’re unaware, you don’t have symptoms. So what’s the alternative? Constant fingersticks? That’s torture. And expensive. And unsustainable. So now we’re supposed to pay for tech to replace the body’s natural feedback system? Brilliant.

And let’s not forget: many elderly patients can’t use CGMs. They don’t understand the alerts. Their kids don’t live nearby. So what? Do we just stop giving them beta-blockers? That’s not patient-centered care. That’s tech elitism.

And why is no one talking about glucagon kits? Or training caregivers? Or teaching families to recognize subtle signs like confusion or slurred speech? Sweating is just one clue. It’s not the whole picture.

Also, the DIAMOND trial? Still recruiting. Not published. Not validated. Don’t treat it like gospel. We’re not in 2026 yet.

And finally-why is this post so aggressively pro-CGM? Who funds this content? Is it Medtronic? Dexcom? Because this reads like a sponsored blog disguised as medical advice.

Wesley Pereira

January 8, 2026 AT 23:29Bro, I’m a nurse on the med-surg floor and I see this daily. Patient gets admitted for CHF, starts metoprolol, insulin sliding scale, no CGM, glucose checked at 0600, 1200, 1800, 2400. They crash at 0300. No one notices. No sweat. No tremor. Just… unconscious. We’re not talking about ‘maybe’ here-we’re talking about code blues in room 412. And yeah, carvedilol is better. But guess what? Insurance won’t cover it unless you’ve failed three others. So we’re stuck playing whack-a-mole with meds and glucose. And patients? They’re tired of being guinea pigs. I’ve seen 3 near-deaths this month alone. It’s not theory. It’s Tuesday.

Pavan Vora

January 10, 2026 AT 14:36India here, and we don’t have CGMs for most diabetics-too expensive. My uncle is on insulin and propranolol for hypertension. He sweats like crazy at night, but he thinks it’s just ‘hot weather’. We started giving him glucose tabs by his bed. Now he wakes up. Simple. No tech. Just awareness. Also, in our village, people say ‘beta-blockers make you sleepy’-they don’t know it’s hiding low sugar. Education is the real medicine here. Not gadgets.

Susan Arlene

January 10, 2026 AT 21:18just because you can't feel it doesn't mean it's not happening

my dad went unconscious once because he thought he was just tired

now he checks before every meal

no fancy tech

just a $10 meter and a habit

you don't need a study to know sweat is your body screaming

Dana Termini

January 12, 2026 AT 18:48I appreciate the depth here. I’ve seen patients on beta-blockers dismiss sweating as anxiety. But it’s not anxiety-it’s a physiological emergency. The key is consistency: check, eat, recheck. Not waiting. Not hoping. Just doing it. It’s not glamorous, but it’s what keeps people alive.

Isaac Jules

January 14, 2026 AT 03:07Wow. Another ‘beta-blockers are evil’ post. Let me guess-you also think insulin causes obesity and CGMs are a scam? 😂 This is why medicine is broken. You take one study, ignore 10 others, and turn it into a cult. Carvedilol isn’t magic. It’s just another drug with side effects. And guess what? Some people can’t tolerate it. But you don’t care. You just want to preach. Go write a pamphlet. I’m out.

Amy Le

January 15, 2026 AT 00:34AMERICA IS BEING DESTROYED BY PHARMA-DRIVEN MEDICAL ABUSE 🇺🇸😭

Why are we letting corporations dictate how we treat heart disease? Carvedilol? That’s a German drug. We should be using American-made meds! And CGMs? Made in China. This is cultural surrender. My grandfather survived on aspirin and willpower. Why can’t we? 🤡

Lily Lilyy

January 16, 2026 AT 00:38You are not alone. I’ve been there. I used to ignore my sweat. Now I carry glucose tabs everywhere. I check before I drive. Before I hug my kids. Before I go to sleep. It’s not about fear. It’s about love. You’re not just protecting yourself-you’re protecting everyone who depends on you. Keep going. You’ve got this.

Indra Triawan

January 17, 2026 AT 13:16It’s funny how we treat our bodies like machines. We forget they’re alive. We want to fix everything with tech. But maybe… the body knows more than we think. Maybe the real problem is we stopped listening. Not the beta-blockers. Not the insulin. Us.

Joann Absi

January 18, 2026 AT 15:38THIS IS WHY WE NEED TO BAN BETA-BLOCKERS IN THE USA 😭🔥

Why are we letting Big Pharma poison our diabetics? 😭

Carvedilol is the answer! But they don’t want you to know because it’s not patented enough! 💔

Wake up sheeple! 🚨💉

Kiran Plaha

January 19, 2026 AT 13:22Thanks for the real talk. I’ve been on metoprolol for 5 years. Just found out I’m hypoglycemia unaware. Started checking before bed. No more midnight crashes. My wife says I sleep better now. Just wanted to say: you’re not crazy for checking. You’re smart.