Key Takeaways

- Never stop phenytoin abruptly; a slow taper reduces seizure risk.

- Common withdrawal signs include anxiety, insomnia, and mood swings.

- Regular blood‑level monitoring helps keep the dose in a safe window.

- Partner with a neurologist and follow a personalized taper plan.

- Stress‑relief techniques and support networks improve coping.

When you’ve been on phenytoin for months or years, the idea of stopping can feel scary. The real worry isn’t just the medication itself-it’s what might happen when the drug leaves your system. This guide breaks down the most common phenytoin withdrawal symptoms, explains why they occur, and gives you practical steps to manage them safely.

Phenytoin is a broad‑spectrum anticonvulsant that has been used since the 1930s to control seizures in people with epilepsy. It works by stabilising neuronal membranes and reducing the spread of abnormal electrical activity in the brain. While it’s effective, the drug can create a physical dependence, meaning the brain gets used to its presence. When the dose drops too quickly, the nervous system can overreact, leading to a withdrawal syndrome.

Why a Withdrawal Can Happen

The body adapts to the steady level of phenytoin in the bloodstream. Two main factors push the need for a careful taper:

- Pharmacokinetic adaptation: Enzymes that metabolise the drug become more active over time, so stopping suddenly leaves a sudden gap.

- Neuronal excitability: The brain learns to function with the drug’s calming influence; removing it too fast can trigger hyper‑excitability, which shows up as seizures or other neurological symptoms.

Because of these mechanisms, clinicians usually recommend a gradual reduction-often called a tapering schedule-rather than an abrupt cessation.

Common Withdrawal Symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms vary widely, but most people report a mix of physical and emotional signs. Below is a quick rundown of what to expect:

- Seizure recurrence: The biggest danger. Even a single breakthrough seizure can be dangerous, especially if you drive or operate machinery.

- Headaches and dizziness: The brain’s attempt to rebalance can cause vascular changes.

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia or vivid dreams are common as the central nervous system readjusts.

- Anxiety and irritability: Mood swings often accompany the physical changes.

- Muscle twitches or tremors: Known as myoclonus, these can be mild or more noticeable.

- Nausea or loss of appetite: Gastro‑intestinal upset isn’t rare during tapering.

Most symptoms peak within the first week of dose reduction and start to fade as the body adapts to the new level. However, any sign of a seizure should prompt immediate medical attention.

How to Taper Safely

Creating a taper plan is a collaborative effort between you, your neurologist, and sometimes a clinical pharmacist. Here’s a step‑by‑step framework that works for most adults:

- Get a baseline serum phenytoin level. Normal therapeutic range is 10‑20 µg/mL. Knowing where you start helps guide reductions.

- Discuss your seizure history and any co‑medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, carbamazepine) that could affect metabolism.

- Set a reduction rate: a common approach is 25‑30 mg every 1‑2 weeks, but the exact amount depends on your current dose and how well you tolerate changes.

- Schedule follow‑up blood tests after each dose change to ensure levels stay within a safe window.

- Keep a symptom diary. Note any headaches, mood shifts, or seizure activity.

- Adjust the schedule if you notice worsening symptoms. Slowing the taper is always safer than speeding it up.

Below is a simple comparison of a “fast” versus “slow” tapering schedule. The numbers are illustrative; always follow your doctor’s specific plan.

| Aspect | Fast Taper | Slow Taper |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 4‑6 weeks | 12‑16 weeks |

| Typical Dose Reduction | 30‑50 mg every week | 15‑25 mg every 2 weeks |

| Seizure Risk | Higher | Lower |

| Common Side‑Effects | Increased anxiety, tremor | Milder headache, occasional insomnia |

| Ideal For | Short‑term use, stable seizure‑free patients | Long‑term users, history of breakthrough seizures |

Coping Strategies During Withdrawal

Even with a perfect taper, the body still needs help handling the transition. Here are practical tips you can start right away:

Medical Supports

- Adjunctive meds: Short courses of benzodiazepines (e.g., clonazepam) can smooth out anxiety and lower seizure risk during the most vulnerable weeks.

- Blood‑level monitoring: Regular serum checks keep you in the therapeutic range and catch accidental overdoses early.

- Vitamin and mineral supplementation: Some studies suggest magnesium and B‑vitamins help calm neuronal excitability.

Lifestyle Adjustments

- Sleep hygiene: Aim for 7‑9 hours, keep a consistent bedtime, and avoid caffeine after noon.

- Stress‑reduction techniques: Deep‑breathing, guided meditation, or gentle yoga can lower cortisol, which often spikes during withdrawal.

- Exercise: Light cardio, like walking or swimming, improves blood flow and endorphin levels without over‑exerting the nervous system.

- Hydration and balanced meals: Staying hydrated supports kidney function, which clears the drug and its metabolites.

Support Networks

- Join an online epilepsy forum. Hearing others’ stories normalises the experience.

- Tell a trusted friend or family member about your taper plan. They can help spot early warning signs.

- Schedule regular check‑ins with your neurologist, even if everything feels fine.

When to Seek Immediate Help

While most withdrawal symptoms are manageable, certain red flags demand urgent medical attention:

- Any seizure activity, especially if it lasts longer than a minute (status epilepticus).

- Severe confusion, hallucinations, or loss of consciousness.

- Persistent vomiting or inability to keep fluids down, which can lead to dehydration.

- Rapid heart rate (>120 bpm) accompanied by chest pain or shortness of breath.

If you notice any of these, call emergency services or go to the nearest ER. Bring a list of your current meds, recent phenytoin doses, and the most recent blood level result.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop phenytoin abruptly if I feel better?

No. Suddenly stopping increases the risk of breakthrough seizures, which can be life‑threatening. A taper, even a short one, is essential.

How long does withdrawal usually last?

Most symptoms peak within the first 7‑10 days after a dose reduction and gradually improve over 3‑4 weeks. Full adaptation can take up to 2‑3 months for some people.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter sleep aids during taper?

Only after discussing with your neurologist. Some antihistamine sleep aids can interact with phenytoin metabolism, potentially raising levels and causing side‑effects.

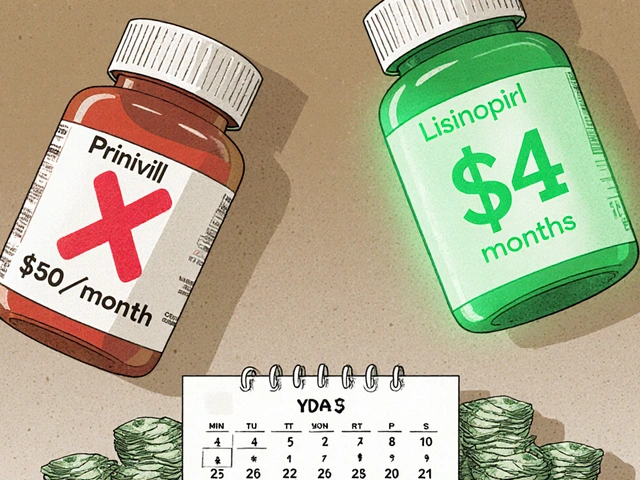

What alternatives exist if I can’t tolerate phenytoin?

Common alternatives include carbamazepine, levetiracetam, and valproic acid. Each has its own profile, so a neurologist will match the drug to your seizure type and health background.

Will my blood phenytoin level drop immediately after I cut the dose?

Phenytoin has a long half‑life (about 22 hours), so levels decrease gradually. Nonetheless, a 25‑30% drop in dose can still cause noticeable symptoms.

Going through a phenytoin taper can feel like a roller coaster, but with a solid plan, regular monitoring, and a few coping tricks, you can navigate it safely. Remember, the goal isn’t just to stop a pill; it’s to keep your brain stable and your life uninterrupted.

Sarah Unrath

October 19, 2025 AT 17:15I was actually on phenytoin for three years and i didnt even think about taper until i read this guide wow thanks for the heads up

Christopher Burczyk

October 20, 2025 AT 15:29While the guide accurately outlines the necessity of gradual tapering, it omits the fact that phenytoin follows non‑linear kinetics, especially at higher concentrations, which can complicate serum level interpretation. Clinicians should therefore employ individualized pharmacokinetic modeling rather than relying solely on fixed milligram reductions. Moreover, concomitant enzyme‑inducing medications such as carbamazepine can accelerate clearance, necessitating more frequent monitoring. The recommended therapeutic window of 10‑20 µg/mL should be contextualized within each patient’s baseline level. Failure to adjust for these variables may increase the risk of breakthrough seizures despite adherence to a nominal taper schedule.

dennis turcios

October 21, 2025 AT 13:42The article does a decent job summarizing common symptoms, but it underplays the prevalence of myoclonus during the early reduction phase. In my experience, even a modest 20 mg cut can trigger noticeable twitches in a subset of patients. If you notice these signs, consider a slower decrement or a short adjunctive benzodiazepine course. Also, keep a meticulous diary; vague recollections rarely help when you discuss adjustments with your neurologist.

Leo Chan

October 22, 2025 AT 11:55Hey folks! Great rundown – just a reminder to pair the taper with good sleep hygiene and light exercise, it really helps the brain settle back into its natural rhythm.

parth gajjar

October 23, 2025 AT 10:09Ah, the drama of withdrawal! One feels as if the neurons are staging a rebellion, each synapse shouting for the missing calm. The mind, deprived of its familiar shield, spirals into a tempest of anxiety. Yet, within that chaos lies an opportunity to rediscover resilience. Embrace the turbulence, let it pass like a storm, and you may emerge steadier.

Kevin Sheehan

October 24, 2025 AT 08:22Phenytoin withdrawal is not merely a pharmacologic event; it is a profound reminder of the brain’s adaptive capacity. When we impose an abrupt void, we force neural circuits to recalibrate under duress, often exposing latent excitability. An ethical approach demands respect for this delicate balance, hence the emphasis on slow tapering. Aggressive shortcuts betray a disregard for patient autonomy and safety. Let the process be guided by patience, not haste.

Jay Kay

October 25, 2025 AT 06:35Honestly, the guide skips over the fact that over‑the‑counter sleep aids can sometimes raise phenytoine levels, causing more trouble than help.

Jameson The Owl

October 26, 2025 AT 03:49The mainstream narrative tells us to trust the doctor’s taper plan, but have we considered who benefits from keeping patients dependent on a single anticonvulsant? Look at the pharmaceutical supply chain – long‑term phenytoin users become a steady revenue stream, and any push toward newer, patent‑free alternatives threatens that flow. Moreover, the data on non‑linear metabolism is often buried in obscure journals, inaccessible to the average patient. This intentional obfuscation ensures that the public remains reliant on repeat prescriptions. It is no coincidence that the guidelines emphasize frequent blood level checks; each test is another touchpoint for the healthcare system to intervene, adjust doses, and justify continued medication. The conspiracy extends beyond economics; it shapes our very perception of what constitutes “safe” withdrawal. By questioning authority and seeking independent monitoring, we can reclaim agency over our own neurochemistry.

Rakhi Kasana

October 27, 2025 AT 02:02Your point about slow tapering is well‑taken, and it aligns with the broader consensus that patient safety must trump convenience. However, I would add that psychosocial support can be just as crucial as the pharmacologic plan.

James Dean

October 28, 2025 AT 00:15Sounds like a solid plan.

Monika Bozkurt

October 28, 2025 AT 22:29The pharmacokinetic profile of phenytoin is characterized by zero‑order metabolism at therapeutic concentrations, which introduces considerable inter‑patient variability.

Consequently, a linear dose reduction may not correspond to a proportional decrement in serum levels.

Therapeutic drug monitoring should therefore be performed at each titration step, with a recommended interval of 2‑3 weeks to capture steady‑state concentrations.

In patients with concomitant enzyme‑inducing agents, such as carbamazepine or phenobarbital, the clearance of phenytoin may increase up to 50 percent, necessitating dose adjustments.

Conversely, inhibitors like ciprofloxacin can precipitate supratherapeutic levels, heightening the risk of toxicity during taper.

The neurophysiological underpinnings of withdrawal–related myoclonus involve transient upregulation of voltage‑gated sodium channels as the drug is withdrawn.

Clinical observations suggest that adjunctive low‑dose benzodiazepines can ameliorate this phenomenon without significantly affecting seizure threshold.

Patients should be counseled on the importance of maintaining consistent dietary protein intake, as fluctuations can alter phenytoin protein binding.

Hydration status also plays a role; hypovolemia may concentrate plasma levels, whereas overhydration can dilute them.

From a neuropsychological perspective, anxiety and irritability often correlate with heightened cortisol secretion during the taper.

Implementing stress‑reduction techniques, such as mindfulness‑based stress reduction (MBSR), has been shown in controlled trials to attenuate these affective symptoms.

Furthermore, engaging in moderate aerobic exercise, for example, 30 minutes of brisk walking three times per week, supports neuroplastic adaptation.

It is advisable to document all adverse events in a structured diary, noting temporal relationship to dose changes, to facilitate evidence‑based decision making.

In the event of breakthrough seizures, rapid reinstatement to the prior tolerated dose is recommended, followed by a reassessment of the taper velocity.

Ultimately, an individualized, data‑driven taper protocol, under close multidisciplinary supervision, optimizes both seizure control and quality of life.

Penny Reeves

October 29, 2025 AT 20:42One cannot overlook the subtle interplay between phenytoin’s half‑life and patient-specific metabolic rate; ignoring this nuance can render a seemingly modest taper dangerously aggressive.

Sunil Yathakula

October 30, 2025 AT 18:55hey bro i totally get the stress of cutting down meds but try to keep a steady routine and drink plenty of water it really helps the body adapt

Catherine Viola

October 31, 2025 AT 17:09It must be emphasized that any deviation from the prescribed taper schedule without direct physician authorization constitutes a breach of medical protocol and may expose the patient to unforeseeable neurological hazards.