When Hurricane Helene hit North Carolina in September 2024, it didn’t just knock out power and flood homes - it also cut off 60% of the United States’ supply of IV fluids. Hospitals scrambled. Elective surgeries were canceled. Cancer patients waited. And for the first time in decades, doctors had to decide who got saline and who didn’t. This wasn’t an anomaly. It’s becoming the new normal.

Why Natural Disasters Are Breaking the Drug Supply Chain

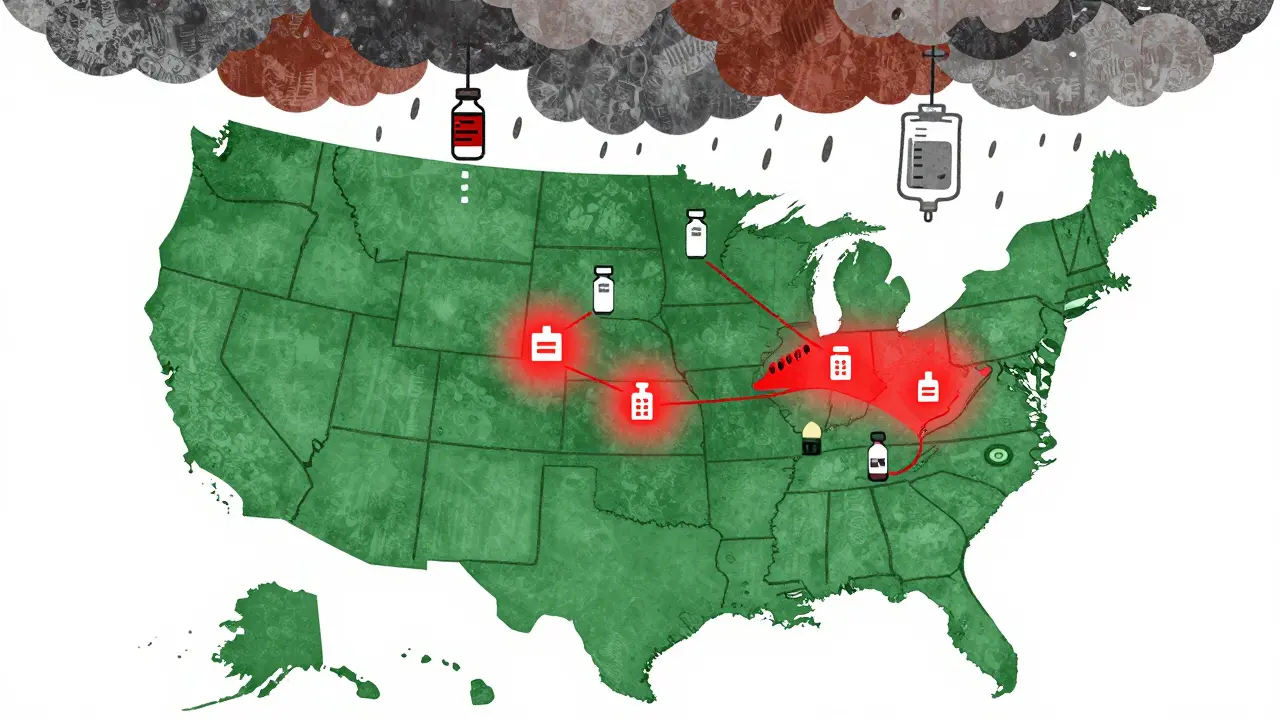

The pharmaceutical industry runs on precision, speed, and concentration. Most of the drugs you rely on - from insulin to antibiotics to IV bags - are made in just a handful of factories. Puerto Rico alone used to produce 10% of all FDA-approved drugs and 40% of sterile injectables. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, those factories were flooded, powered down, and offline for months. Insulin shortages lasted 18 months. Saline took 14 months to fully recover. Today, 65.7% of U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities are in counties hit by at least one weather disaster between 2018 and 2023. Hurricanes are the biggest threat, causing nearly half of all climate-related drug disruptions. But wildfires, floods, and even extreme heat are closing factories too. The problem isn’t just the storm - it’s what happens after. Power grids take months to repair. Supply chains for raw materials snap. Equipment that can’t be replaced quickly stalls production. Take Baxter’s plant in North Cove, North Carolina. It made 1.5 million IV bags a day. One storm. One flood. And suddenly, the entire country was running on fumes. That’s not a fluke. It’s the design. The industry relies on just-in-time inventory. No backups. No buffer. One factory down, and patients pay the price.The Hidden Geography of Risk

It’s not random where these factories are. They cluster in places with cheap labor, tax breaks, and infrastructure - not because those places are safe from climate disasters. Western North Carolina is now a critical vulnerability zone. One town, Marion, houses the main IV fluid plant. Another, Spruce Pine, supplies 90% of the high-purity quartz used in medical device chips. If that one town gets hit, it doesn’t just affect one drug - it breaks dozens of devices used in hospitals nationwide. Puerto Rico’s role in drug manufacturing hasn’t fully recovered. Even today, it produces 80% of the U.S. insulin supply. That’s a single point of failure. One storm, one power outage, and millions of diabetics are at risk. The FDA says 78% of sterile injectable drugs in the U.S. have only one or two manufacturing sites. That’s not efficiency - it’s fragility. And it’s not just the U.S. The 2018 earthquake in Kermanshah, Iran, killed 700 people and injured 10,000. Hospitals ran out of antibiotics and painkillers. But because Iran’s drug production is more spread out, the shortage didn’t cascade the same way. The U.S. system is designed for cost, not resilience. And climate change is making that design deadly.

What Happens When the Drugs Run Out

When IV fluids disappear, it’s not just about hydration. It’s about chemotherapy drips, antibiotics, emergency resuscitations, and newborn care. Hospitals started rationing. Some used expired bags. Others diluted solutions - a risky workaround that can cause infections or organ damage. In 2022, when flooding hit Abbott’s infant formula plant in Michigan, the shortage lasted 8 weeks longer than it should have. Parents drove hours to find formula. Some mixed homemade recipes - with tragic results. Cancer drugs are especially vulnerable. Many are older generics - cheap to make, but with razor-thin profit margins. Manufacturers don’t invest in backup lines because there’s no financial incentive. The American Cancer Society found that 40% of life-saving cancer injectables have been in chronic shortage since 2017. Climate disasters just make it worse. And it’s not just hospitals. Pharmacies can’t stockpile enough. Insurance companies won’t pay for extra inventory. The system is built to run on empty shelves - until it doesn’t.What’s Being Done - And Why It’s Not Enough

The FDA now officially lists natural disasters as a top cause of drug shortages. In 2024, they launched the Critical Drug Resilience Program, offering faster approval for manufacturers who spread production across three geographically separate, climate-resilient zones. That’s a start. But only 31% of major drug companies have taken meaningful steps to reduce risk. Some hospitals are getting smarter. Mayo Clinic spent nine months mapping every supplier - from the raw chemicals to the plastic bags. When a storm hit, they knew exactly which drugs were at risk and where to find alternatives. Their response time dropped by 65%. But most hospitals - especially small ones - don’t have the staff or budget to do this. The Strategic National Stockpile is now piloting emergency reserves of IV fluids and insulin in hurricane-prone states. During Helene, these reserves cut shortage duration by 40% compared to Maria. That’s progress. But the stockpile holds enough for only a few weeks. It’s a Band-Aid, not a solution. AI is helping too. Companies like Sensos.io use weather models to predict which plants will be hit - sometimes 14 days ahead. Hospitals that used those warnings were able to secure emergency stockpiles. But only a handful of health systems have access to this tech.

Mel MJPS

January 28, 2026 AT 07:47My mom’s on chemo and they had to switch her IV saline brand last month because the usual one was gone. She got a rash from the substitute. No one told us it was because of a hurricane in NC. It’s terrifying how little we know about what’s really keeping us alive.

I just hope this doesn’t become the new normal. We’re talking about people’s lives here, not supply chain KPIs.

Mindee Coulter

January 29, 2026 AT 08:17